Daniel Johnson Dam and the Manic 5 Generating Station—Symbols of Modernity in Quebec

par Harvey, Christian

The Daniel Johnson dam and the Manic 5 generating station, a hydroelectric complex located 214 km north of Baie-Comeau in the Côte-Nord region of Quebec, remain strong symbols of Quebec’s hydraulic wealth and technical prowess for a majority of Quebec’s citizens. The emblematic power of these facilities might be summed up in the expression “We can do it after all!” NOTE 1 On the one hand, this treasure of Quebec’s heritage—the world’s largest multiple-arch and buttress dam—is the expression of undeniable know-how put into action by the engineers of Hydro-Québec and Quebecois engineering consultants. On the other hand, this hydroelectric complex, more than any other, embodies a society that has definitively reclaimed control of development of its primary source of wealth—namely, its hydraulic resources—for the improvement of the greater common good.

Hydroelectric Power—From the Beginnings to Nationalization

In the late 19th century, electric power, which by this time had been around for quite a while, began to be produced in North America on a large scale NOTE 2. In Quebec, large-scale production began in earnest in 1878, when J.-A.I. Craig made the first attempt to produce outdoor electric lighting using an arc lamp NOTE 3. Various firms would subsequently try to corner the market to produce electric lighting for the streets of Montreal, drawing primarily on thermal power.

Quebec, endowed with a wealth of hydraulic power, made a resolute move towards producing hydroelectricity with construction of the first generating stations—namely, Montmorency Falls in Quebec City (1885), Lachine (1897), Chambly (1898) and, the most imposing structure of them all, Shawinigan, which began generating power in 1902. Until 1963, Quebec relied on a supply network dominated by a handful of firms that enjoyed a monopoly in the region. This supply network provided a favourable environment for industrial development in the province, particularly in the pulp and paper sector, but was hard-set to provide service to remote areas.

Hydro-Québec

The Quebec Hydroelectric Commission, usually referred to as Hydro-Québec, was established in 1944 for the purpose of administering the acquired assets of Montreal Light, Heat and Power, which, although criticized by some, had served the greater Montreal area until that time. The mandate of the newly-formed, government-owned corporation was to provide consumers with the best possible rates while maintaining a fiscally sound business. According to Clarence Hogues et al, between 1944 and 1962, Hydro-Québec “...was able to effectively meet growing needs for power in both metropolitan Montreal and the outer regions [of Quebec]—such as Gaspésie, Chibougamau, western Quebec and Côte-Nord— where private companies were either unwilling or unable to extend their services.” NOTE 4

Toward this end, Hydro-Québec initiated construction of new hydroelectric plants in Bersimis (1 and 2), Beauharnois (2 and 3), and Carillon, laying the way to provide electricity to families and factories located in poorly serviced areas. Henceforth, Hydro-Québec sought to benefit from the cumulated power of the Manicouagan and Outardes rivers, located in the Côte-Nord region. Completion of this monumental project would coincide with a complete government takeover of hydroelectricity, leading to early elections in 1962 that amounted to a popular referendum on the issue of public ownership of the hydroelectric utility.

“Maître chez nous” and Nationalization of the Hydroelectric Utility

In 1961, under the impetus of Quebec’s minister of natural resources René Lévesque, a public debate on the issue began to emerge. In Lévesque’s own words, the hydroelectric sector at this time constituted an “unlikely and costly mare’s nest.” NOTE 5 With electric power provision administered by a public utility, it would become possible to develop an integrated network across the province, particularly in remote regions, while reaping the benefits of the most lucrative services. In 1962 Quebec’s premier at the time, Jean Lesage, called an election around the issue of nationalization of hydroelectric services. In a now-famous speech, he stated, “We must give back to the people of Quebec that which belongs to the people of Quebec, their greatest treasure: hydroelectric power. And we must do it now. Tomorrow, it will be too late. It is now or never if we are to be masters in our own home.”

In 1963, with the election victory of Jean Lesage’s Liberals, nationalization went forward by means of a series of buyout offers presented to the various private firms that were providing hydroelectric power at the time. Practically speaking, however, it would be several years before Hydro-Québec could create a truly integrated network throughout Quebec, as operations at the many private companies that had been acquired were quite varied.

Construction of the Manic 5 Generating Station and the Daniel Johnson Dam: Expertise in Action

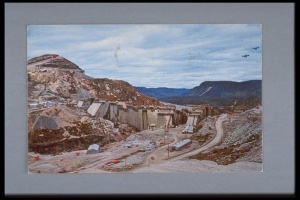

In the 1950s, with work underway in Bersimis (Côte-Nord ), Hydro-Québec’s engineers turned their attention to developing the vast hydraulic potential of the Manicouagan and Outardes rivers. Some preliminary construction work was undertaken. In 1956, a dam was erected at the mouth of the Toulnustouc river where it flows into Lac Sainte-Anne for the purpose of regulating flow of the Toulnustouc river, the primary tributary of the Manicouagan river. Three years later, in 1959, construction began on a 210-km road that would provide access to the complex.

In August 1960, Hydro-Québec unveiled the details of the Manic-Outarde construction project. Production from the generating station was destined “...to provide power mostly to southern Quebec and particularly the greater Montreal area.” NOTE 6 Calculations underestimated the potential output and were therefore adjusted upward. Work on Manic 5 began in September 1960 with the start of construction of the dam that would serve to “...regulate the flow of water from the vast reservoir planned for in the design drawings in order to obtain optimal output from the generating stations that [would] be built downriver along the Manicouagan.” NOTE 7 From May to September 1961, two diversion tunnels were erected to divert the flow of the river so that the area that would serve as the base of the dam could be dried out. Construction work would take two years. On 22 September 1962, the first concrete was poured for construction of a dam that would be completed in the spring of 1964.

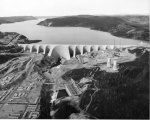

The expertise of Hydro-Québec’s engineers, confirmed with development of the Carillon hydroelectric facility on the Ottawa River, made them the obvious choice for this type of work, along with a Quebecois engineering and consulting firm, Surveyer, Nenninger et Chênevert. The Manic 5 dam is the world’s most imposing multiple-arch and buttress dam. 1,314 metres long and 214 metres high at its highest point, the dam forms a reservoir covering 2,100 square km of surface area, supplying water to power the turbines of the generating stations located downriver, among them the Manic 5 stations, which produced 1,292,000 kilowatts (or 1,292 MW) when they began operating in 1970. Later, with the modernization of equipment that came about in the 1980s, output at the station was increased by 18% to 1,596 MW. In addition, a new generating station, named Manic 5 PA, began operating in 1989 with output of 1,064 MW. Overall, then, the Manic 5 complex today produces a total of 2,660 MW, compared to 5,616 MW for LG2 on the La Grande River at James Bay, or 675 MW for the Gentilly-2 nuclear plant.

The Name Daniel Johnson

Originally, the dam built at Manic 5 was to be named Duplessis Dam in honor of Quebec premier Maurice Duplessis. However, an unfortunate event led to a change of plans. On the eve of the dam’s inauguration, scheduled to take place on 25 September 1968, Quebec’s premier Daniel Johnson, who had come to the site to take part in the ceremonies, died during the night. Celebrations were of course cancelled.

It was not until a year later, on 25 September 1969, that Johnson’s successor Jean-Jacques Bertrand finally inaugurated the dam, which was called Daniel Johnson Dam in honour of Bertrand’s predecessor who had died on the site. The complex on the whole would still be called Manic 5.

The 735-kW Power Line

The primary innovation of the Manic-Outardes, however, was implementation of the 735-kilowatt electrical transmission line, a first in the industry, establishing Hydro-Québec’s reputation as a technical innovator around the world. According to Hogue et al, “...it was through high-voltage electrical power transmission that Hydro-Québec made a name for itself in the world of research.” NOTE 8 To develop this technology, the government-run business had to “...use computers on a massive scale and run numerous trials in US and European labs to determine the characteristics of the power lines.” NOTE 9

With this new technology developed by Hydro-Québec, it became possible to transport electricity over a great distance without excessive loss of power. Thus, electricity produced in Côte-Nord region could be transported to the very densely populated regions of southern Quebec. On 21 September 1965, the power line linked the Manicouagan region to the town of Lévis, crossing the St. Lawrence via Île d’Orléans. Service to Montreal was established on November 21 of the same year. Continuing in the same vein, in 1967, Hydro-Québec established the Institut de recherche en électricité du Québec (IREQ) in Varennes, an organization that would become renowned well beyond the borders of the province.

A Symbol of Modernity in Quebec

In 1962, the Maître chez nous election campaign run by Jean Lesage’s Liberals, made its mark in the minds of voters with, at its centre, a project to nationalize Quebec’s hydroelectric resources. Although it had been launched prior to this political event, construction of the Manic 5 generating station and the Daniel Johnson dam meshed with the theme of the election campaign and with the momentum that had spread throughout the province. The project thus became a symbol of the Quiet Revolution in action. The written media and television conveyed the images and the details of this gargantuan construction project. In 1967, the construction project was a big part of the display at Quebec’s pavilion at the Montreal world exposition.

In 1966, in a song called simply La Manic, Quebecois songwriter Georges Dor sang of the hardships endured by workers living in trailer towns built to house them as they battled boredom (si tu savais comme on s’ennuie) and the effects of prolonged separation from their families and loved ones, who had remained behind in the dirty, crisscrossing streets of Montreal (les rues sales et transversales de Montréal) or in other populous cities and towns of southern Quebec. This song, covered in 1998 by Bruno Pelletier, was hugely successful when it first came out and became an emblematic representation of the Manic 5 project. In 1969, an automobile called Manic GT was also built, but met with very little success. Finally, in 1971, songwriter Claude Gauthier alluded to the Manic 5 projects in his well-known song, Le plus beau voyage, ode to an unborn nation, which ends with the phrase Je suis l'énergie qui s'empile, d'Ungava à Manicouagan (I am the power building up from Ungava to Manicouagan).

The government of Quebec now places more emphasis on the value of the province’s industrial wealth in the form of Quebec’s electrical generating stations NOTE 10 and on the government corporation Hydro-Québec, which organizes guided tours of the Daniel Johnson dam (and other facilities) during the summer months from June 24 through August31. The two-hour tour offers a presentation of the stages of construction of the dam and describes operations of the Manic 5 generating station, including a visit to the turbine room and a stop atop the crest of the dam.

Celebrations in observance of the 50th anniversary of the Quiet Revolution also featured Manic 5 through a blossoming of commemorative activities that gave new life to this still-robust and particularly meaningful symbol of Quebec’s recent past.

Manic 5—A Peerless Reputation

Subsequently, Hydro-Québec’s major hydroelectric projects, such as the one at James Bay, while they too left their mark on the collective imagination and history of Quebec, met with more equivocal recognition. Environmental issues and claims by first nations (particularly the Cree Nation) have cast a shadow on such mega-projects, despite the importance generally accorded to hydroelectric development in Quebec by Quebecois historians in their historical overviews. NOTE 11

Christian Harvey

Centre de recherche sur l’histoire et le patrimoine de Charlevoix

NOTES

1. Quoted passages translated by Mark Stout. Original French passages excerpted from Clarence Hogue, André Bolduc and Daniel Larouche, Québec, un siècle d’électricité, Montreal, Libre expression, 1979m p. 269.

2. Paul-André Linteau, René Durocher and Jean-Claude Robert, Histoire du Québec contemporain : De la Confédération à la crise, Montréal, Boréal express, 1979, p. 357.

3. Hogue et al, op. cit., p. 19.

10. See, for example, the Website (in French only) for Quebec’s department of Culture, Communications and the Condition of Women (Ministère de la Culture, des Communications et de la Condition féminine du Québec).

11. In particular, Paul-André Linteau, op. cit.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Chute Montmorency - P

Chute Montmorency - P

ont de chemin d... -

Jean Lesage, René Lév

Jean Lesage, René Lév

esque et Daniel... -

Kiosque d'Hydro-Québe

Kiosque d'Hydro-Québe

c, Pavillon du ... -

Le barrage Daniel-Joh

Le barrage Daniel-Joh

nson

-

Manic: d'imposantes i

Manic: d'imposantes i

nstallations hy... -

Manicouagan 5. Le plu

Manicouagan 5. Le plu

s grand barrage... -

Maquette de pylone, P

Maquette de pylone, P

avillon du Québ... -

Maquette du barrage D

Maquette du barrage D

aniel-Johnson (...

-

Parc des roulottes

Parc des roulottes

-

Pavillon du Québec à

Pavillon du Québec à

Toronto, 1971.... -

Vue aérienne du barra

Vue aérienne du barra

ge et de la cen... -

Vue générale des trav

Vue générale des trav

aux